I was quoted in today's LA Times article on Metro's (MTA's) proposed fare increase:

I was quoted in today's LA Times article on Metro's (MTA's) proposed fare increase:

"Rail gives greater speed, it's more comfortable and it has higher capacity than buses," said Darrell Clarke, co-chairman of Friends 4 Expo Transit, which has been pushing for the line from downtown to Culver City. "Buses are stuck in traffic."

I'm disappointed the article was cast as bus vs. rail, though, framing the issue as:

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority today will consider approving a series of large fare increases that would hit bus riders particularly hard at a time when officials are spending $1.5 billion for a network of new rail lines.

Construction costs for rail come from different sources than operations, and operating costs for rail are less than for buses. In Metro's FY07 Budget (Appendix 15, pp. VII-46-47), buses cost $0.61 per passenger-mile, compared to light rail's $0.49 and the subway's $0.47.

This is consistent with national statistics, and makes sense: the largest cost of running transit is vehicle operators, and one 3-car Blue Line train carries more passengers than six regular buses (or four of the new articulated buses). (Click for more.)

It's not either-or; we need both rail for main high-speed corridors and buses to fill in the gaps and provide local service. Rail is also more attractive to get people out of their cars and to attract the transit-oriented development Los Angeles needs to handle population growth without completely choking on traffic.

On the fare increase, many transit advocates recognize Metro's costs have been increasing for labor, fuel, and expanded service, while fares have been held flat for a decade. Like the LA Times editorial today, we seek a middle ground between no increase and Metro's original proposal:

Big transit systems in the U.S. get 38% of their operating revenues from fares, on average, while the MTA went from 32% before the decree to 24% today. If transit riders don't start paying their fair share, the agency will have no choice but to cut bus and rail service, which won't benefit anybody.

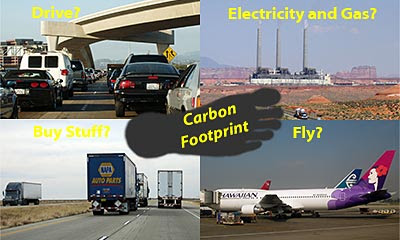

An ideal solution would find new sources of transit operations funding from sources like gas taxes, parking fees, carbon taxes, or congestion pricing, to mitigate for the externalized costs of automobiles.

Updates: I just spoke about this with Patt Morrison on KPCC.

Here's the LA Times on the final compromise by county Supervisors Gloria Molina and Zev Yaroslavsky that was adopted:

... the original increase, which would have raised the cash fare for both rail and bus to $2 per ride from $1.25. The monthly pass would have increased to $120 from $52 over the next 19 months.

Instead, ... fares will increase to $1.50 by July 1, 2010, then $1.80 by 2012. The $3 daily pass will jump to $5 by 2008, $6 in 2010 and $7.25 two years later. The $52 monthly pass will go up to $62 in 2008, $75 in 2010 and $90 in 2012.

A special [off-peak] 25-cent fare will be established for the disabled and seniors 65 and older. The fare would be in effect 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. and after 7 p.m. on weekdays, and all day Saturday, Sunday and federal holidays.

Be sure to read Steve Lopez' column, especially Martin Wachs' comments:

"There's no question that in a metro area like L.A., a transit system cannot be sustained" by current formulas, said Martin Wachs of the Rand Corp. "You need some form of tolls or parking or gas increases, with a transfer of funds from auto users to transit users."

He and Brian Taylor of UCLA's Institute of Transportation Studies support a variable fare system, saying it's illogical to charge a flat $1.25 for a bus ticket regardless of whether the rider goes 30 miles or three blocks.

Southern California Transit Advocates (So.CA.TA) has an extensive discussion of their fare recommendations and the final Metro plan.